Meet the human family

Boyce Rensberger

(1/2025) With our questionable tradition of classifying people into categories that we call races, you could be forgiven for thinking that we human beings belong to a rather varied species. Actually, we’re not all that diverse if you compare us to the different kinds of human beings we may actually have encountered in the prehistoric past.

At least eight other species of humans have lived on Earth during the time since our own species—Homo sapiens—appeared. That was roughly 250,000 years ago. The others are species that anthropologists consider to be enough like us that they belong to our genus—Homo (Greek for "man")—but that were different enough that they qualify as separate species.

|

|

|

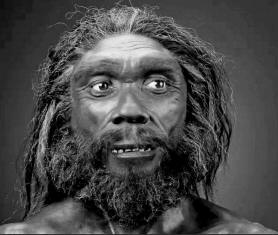

The reconstructed faces of our relatives, Homo heidelbergensis (left)

and Homo neanderthalensis. The Smithsonian’s John Gurche created these

by layering clay on casts of fossil skulls. Skin color is conjectural. |

They all had bodies pretty much like ours. They all walked on two legs. They all had hands and made tools. But their brains and faces were different. Maybe we would call them "people," but some of those human beings were so different that it’s not clear we would have wanted to share a meal with them.

Neanderthals are one of the others. These people weren’t so different from us—close enough, for example, that we did mate with them many times. More about that shortly.

Quite possibly, each species of human kept to itself. Most of the time. After all, the populations of some human groups are thought to have been quite small, rarely expanding beyond limited territories.

If we extend the time horizon to the last few million years, at least 20 different species of human beings have lived on Earth. Each of them survived for a few hundred thousand or a few million years. Then, one by one, each died out. Except for one.

Here are just a few examples of our ancient relatives who lived during our 250,000 years and who we may have met.

Homo erectus—These folks were the most successful human species ever, judging by how long they survived. The earliest evidence of them is from two-million-year-old fossils, and the latest from a mere 110,000 years ago. That’s ten times longer than we have been in existence. H. erectus arose in Africa and is the first kind of human to migrate out. They spread into southern Asia and went as far as modern China and the islands of Indonesia.

Homo floresiensis—These are the diminutive people nicknamed Hobbits who arose around 100,000 years ago and survived until a mere 18,000 years ago. Found so far only on the Indonesian island of Flores, they stood only three and a half feet tall and had very small brains. But they made and used stone tools, hunted dwarf elephants and may have used fire. It is not clear what their ancestor species was, but it does seem that they and the elephants shrank because of a known phenomenon called island dwarfism. We probably didn’t meet them, but they are such a curiosity that I couldn’t leave them out.

Homo heidelbergensis—These people, descendants of H. erectus but with larger brains, began around 700,000 years ago and were the first to move into Europe, learning to live in colder climates. They knew how to control fire. They built shelters of stone and wood. They had impressive brow ridges, which gave them a rather forbidding look. But we could have interacted because our species overlapped with theirs in Europe for 50,000 years. They died out around 200,000 years ago. They were the last common ancestor of today’s people and the next two groups.

Homo neanderthalensis—You may think you know about these guys, the Neanderthals. But abandon any brutish stereotypes you may have. These folks had brains as big as ours, developed a variety of stone tools, hunted large game, made and wore clothing, buried their dead and, at least in one documented case, laid flowers in a grave. They probably could speak.

They were such close cousins that during the 200,000 years we both lived in Europe we interbred with them numerous times and produced healthy children. All of us who have ancestry from Europe or Asia are offspring of those matings. Between 1 and 3 percent of our genes were inherited from Neanderthals. People of African ancestry share much fewer Neanderthal genes. Moreover, we do not all share the same set of those genes. My Neanderthal genes are probably not the same ones that you have. If you add up the different sets of genes found in living Europeans and Asians, it turns out that modern humans carry as much as one third of the total Neanderthal genome.

The ability of genome scientists to produce this knowledge has recently gone a step further. They have now pinpointed when interbreeding began—47,000 years ago. Also, they have found that this happened many times over a period of 6,000 to 7,000 years. This span begins at roughly the time modern humans, who evolved in Africa, migrated into Europe where they met the Neanderthals. It ended when the last Neanderthals died out.

Denisovans—These people were closely related to the Neanderthals but were genetically different enough to be considered a separate species. Named for the site in Siberia where they were first found, these folks emerged about 370,000 years ago and continued until about 30,000 years ago, basically paralleling Neanderthal dates. It seems likely that both species evolved from Homo heidelbergensis but migrated in opposite directions, Denisovans to the east and Neanderthals to the west. Parts of the Denisovan genome survive in people from Melanesia such as New Guinea and the South Pacific islands.

You get the picture. People just like us could have met people who were quite different from us. Your guess is as good as mine as to how we would have treated them. If facial features are a guide, study the pictures above.

Boyce Rensberger retired to Frederick County after some 40 years as a science writer and editor, primarily at The Washington Post and The New York Times. He welcomes feedback at boycerensberger@gmail.com.

Read past editions of Science Matters

Read other articles by Boyce Rensberger